Eight Weeks in Isolation

With our current global pandemic, people all over the world are in isolation. Depending on where you live, you may have been sheltering-in-place for four weeks. Others have been in isolation even longer. Some are cooped up in small apartments in big cities. Others are in spacious suburban homes. The luckiest folks (in my opinion) are enjoying life on farms or vacation homes out in the country.

For almost eight weeks, I’ve been on Kosrae, a small island in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. I arrived here on March 6th. I planned to stay here for three days, with a ticket to fly to Majuro in the Marshall Islands on March 9th. Without warning, the Marshall Islands closed its airport to all international travelers on March 8th. That’s how I got stuck here.

Since I started posting stories and photos about Kosrae, friends have emailed questions about what my life here is really like. Today, I’ll try to answer those questions. If you still have questions when I’m done, please post a comment or email me.

Kosrae is about the size of Nantucket. But instead of being a resort island with million-dollar homes, ritzy golf courses, and photogenic sand dunes, Kosrae is an extinct volcano covered with dense jungles, fringed by mangroves, beaches and reefs, and home to 6,600 people living in humble villages. Unlike Nantucket, which is 50 km from the mainland, Kosrae is 550 km from its nearest neighbor Pohnpei, which is yet another small, isolated island.

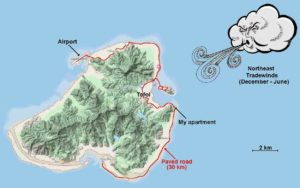

Click on the map above. There’s a paved road that runs along the east side of the island. This is the breezy side of the island where most Kosraeans live. My apartment is 4km from Tofol, Kosrae’s capital. So what’s in Tofol? The College of Micronesia (aka COM), Kosrae’s high school, the hospital, the post office, the police station, the power plant, the telecom center, a few shops, the Bank of Guam with an ATM, a diner where you can get lunch, and a few government offices. In other words, there’s not much in Tofol. For an island of 6,600 residents, what more do you need?

Kosrae’s High School and the COM share a campus in Tofol. They also share a gymnasium. Kosrae’s Historic Preservation Office is in the gymnasium. I volunteer for all three of these organizations. I spend about three days a week in the little valley to the right. (Remember to click on any photo to zoom in.)

This is my apartment. It’s faculty housing for COM’s instructors. I live on the top floor. Another COM professor lives downstairs with her husband. My two-bedroom apartment is 58 m² (624 sq.ft), That’s plenty big enough for me. COM says that I can live here until at least September, which is good because I might be here for a while.

It’s a simple home with the basics. Here’s my kitchen and my desk. Thankfully, I have internet. It’s slow, but good enough to send emails, read the news and maintain this blog. I have two bedrooms and a bathroom down the hall to the left. My balcony looks out over the mangroves. A short path leads through the mangroves to my beach and the reef.

I love the ocean, but I can’t sit on a beach day after day and just relax. I have to have something to do. So, as soon as I realized that I was going to be in Kosrae for a while, I went over to the COM and volunteered as a part-time instructor. At first, the dean and his staff didn’t know what to do with me. After I submitted a formal proposal and syllabus, Dean Mike realized that I was serious about teaching geology and seismology (for free!). He quickly put me to work.

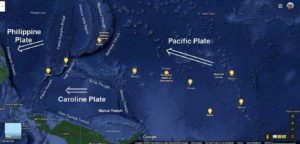

The first week that I was in Kosrae, I gave a one-hour presentation to COM’s faculty and student body on Global Tectonics, Pacific Island Geology and Kosrae’s Environmental Hazards. The purpose for this talk was to explain how Kosrae fits into the big picture of Pacific island formation, how Yap, Chuuk, Pohnpei and Kosrae were created, and what Kosrae’s future will be. Like many Pacific Islands, Kosrae is threatened by rising sea levels and the resulting beach erosion.

Word of my talk got around. After COM was closed by decree from Pohnpei, the high school asked me to give this same talk four times to each of the grades. Next week, I’ll be giving the same talk again to the Kosrae Island Resource Management Authority (KIRMA).

At the high school, I got to know the school principal (Scott Nena) and some of his staff, shown here. They reworked their school calendar, setup a classroom for me and got the students organized. They were wonderfully helpful and friendly. Although I was just a volunteer, they paid me liberally in coconuts, bananas and tangerines.

Principal Nena says that he needs instructors to teach Language Arts (Reading, Writing, and Grammar), Physics, PreCalculus, Algebra, World Studies, American History, Civics and Government, Anatomy, Chemistry, Biology, Business Accounting, and Computer Science. So, here’s a message to all the professors and instructors who read this blog: If you’re interested in living and working in Kosrae — where the cost of living is low and the quality of life is high — please send an email to Principal Scott Nena Salary is dependent on qualifications and degrees. Housing is provided. Teachers are expected to stay at least a year and hopefully longer. COM also has faculty positions open.

Six weeks ago, I had a couple of beers with the folks from Kosrae’s Historic Preservation Office (KHPO). Since then, they’ve become my primary “employer”. Once or twice a week, the KHPO staff takes me to archaeological ruins to ask me questions like “Which quarry did these rocks come from?” “How was this cave formed?” “Are these rocks naturally shaped like this, or were they carved by humans?” “How much do these rocks weigh?” I’ve seen a lot of Kosrae, often hiking deep into the jungles where no one ever goes. Young guys with machetes lead the way to carve a path through the underbrush. Shown here are the Lelu Ruins. They’re about 800 years old and involve tons of rocks transported from other parts of the island. Most of it is columnar basalt, which is heavy stuff. It’s a fascinating mystery as to how these massive rocks got here.

There’s a proposal to build a road across the middle of the island. I volunteered to help with the feasibility study. This required boulder hopping and bushwhacking my way up the route where the new road is supposed to go, to see what sorts of rocks were going to be supporting the road bed. As before, I was accompanied by local guides equipped with machetes.

I came back with bad news. The valley through which the cross-island road is proposed is full of a hydrated clay called Smectite. It’s the result of a million years of chemical weathering of volcanic ash. It’s not a good material to build a road on because it expands when wet and contracts when dry. A road built on this clay will crack and break. Landslides will be a problem, too. Based on my recommendations, I think the governor and his staff have shelved the idea of a cross-island road.

Another project I’m working on is for the new Covid-19 isolation and care facility next to the hospital. After the undergrowth was bulldozed away, I was asked to do a geotechnical analysis to determine if this is a good site for a one-story prefab medical unit on a cement slab. I had good news for the hospital. Although there’s Smectite in the soils at this site, it has sufficient sand and organic matter mixed into it that it will provide an adequate base for a one-story structure. The nearby hill will, however, require some buttressing to prevent a possible mudslide. The chief engineer was glad to have my input.

I know how lucky I am to be here. Getting marooned in a remote place is a welcome excuse to get involved. All these volunteer projects are a great way to get to know the Kosraeans, to see their island and to make a difference. I’m very impressed by what friendly, welcoming people Kosraeans are and by what a paradise Kosrae is.

On Sundays I go to church. There are 14 churches on this island and everyone goes to church. Kosrae’s churches are a good place to meet people. For example, I met the engineers who were looking for a geologist to test the soils for their new hospital site at church.

Every church has a choir. Some are better than others. Click here to listen to one of the local choirs sing their offertory a capella. To get the full effect, turn your computer’s volume up as high as possible.

Oops, I should have warned you that I don’t go to this church to hear the choir.

With no Covid-19 here, Kosrae is a very sociable place. All of the restaurants are open. Here’s the kitchen staff at Bully’s Restaurant, which is connected to the Pacific Treelodge Resort. Their chefs make great food, both local and western. The setting on the banks of the mangrove estuary is absolutely gorgeous. I often meet here with my colleagues and co-workers for drinks and dinner in the evening.

Since there aren’t many supply boats coming to Kosrae these days, we’re fending for ourselves. I eat lots of local fruits. My neighbor sells me coconuts for 25¢ each, and shows me how to open them and eat them.

Besides coconuts and bananas, another local food that I’ve come to love are Kosrae’s tangerines. They’re green when ripe and bright orange inside. They’re juicy and delicious. They’re also much cheaper than the imported fruits that are no longer available at the grocery stores.

I’ve been learning Kosrae’s fishing technique known as sul. For sul, you need sturdy shoes, a headlamp, a basket and a big stick (or a machete). You go out at night at low tide and stalk quietly through the tide pools where the fish are sleeping. When you see a fish big enough to eat, you whack it on the head and put it in your basket. If you’re good, you can catch a dozen fish in 20 minutes. An alternate technique is just to buy fish from the dock when the local boats come in. I’ve come to appreciate just how good really fresh fish can be.

On a practical matter, many of you have emailed to ask about transportation on Kosrae. Because it rains hard 2 or 3 times a day, bicycles and motor cycles are not popular. Most of the vehicles are used cars or pickups imported from Japan. Kosraeans drive like Americans on the right side of the road. Their Japanese vehicles have steering wheels are on the right. This makes the driving a little odd. But with a maximum speed limit of 25 mph, traffic accidents are rare.

Not knowing how long I’m going to live here, I haven’t invested in a car. A car is hardly necessary, though. Kosrae is one of the easiest places in the world to hitch hike. When I want to go somewhere, I walk out to the road and stick out my thumb. I usually get a ride within a minute.

Kosraeans’ are so generous and hospitable that they often go out of their way to deliver me to my destination. One time I was picked up by a car that was on its way to the hospital. In the passenger seat was a man bleeding from a wound to his hand. The driver offered to take me to my destination first, before taking his friend to the hospital. “What?!” I laughed and insisted that we go to the hospital first. This just shows how far the Kosraeans will go out of their way to help a stranger.

By Friday, I will have been in Kosrae for 8 weeks. The time has flown by. I’ve met 100’s of people and made many friends. In this community of 6,600, we all feel as though we’re sheltering in place together. United Airlines says that they might send a plane sometime next month to evacuate the remaining people who want to leave Kosrae. But I don’t think I’ll be on that flight. Next week, Dean Mike wants to talk to me about a possible teaching contract for next fall.

Thanks for reading this long blog all the way to the end. I send my prayers and best wishes to all of you in the rest of the world. Thanks for social distancing. Stay healthy!

Stay safe!!!

Sounds pretty blissful to me!!

Thanks Nick. That was a wonderful recap of what you have been doing. Lovely to be embraced by a community and to be able to offer a valuable service. I bet they would love for you to marry a local so you would stay. (ha ha). This was told to me while I was a volunteer in Nepal. I made note of the HS principal in case I decide to teach math/knitting/art once again. Looks like paradise and a great way to learn more geography.

Have you bumped into another expats living on the island?

Nick,

Thanks a million for your blog. This is a great perspective and a vicarious travel trip for us. We arrived back in the states on March 10 from Auckland. We thought, just in time, but now the Kiwis seem to have beaten the COVID virus and now we could be stranded there instead of our condo in Minneapolis. Timing is everything.

We have sheltered in place and are mostly OK with it. We adapt, wearing masks on our fewer trips to the stores. Have meetings on Zoom or Webex – 3 of them today and trying to stay in touch with friends by phone, email, or even a weekly “hallway happy hour” with our across the hall neighbors, maintaining appropriate distance, of course. Ironically, it has even resulted in reuniting with old friends. The world has changed and will likely never return to what we have grown up with – a truly pivotal catastrophe. Plenty of misinformation being circulated here, including some by our own president. Most people take this threat seriously and play it safe, realizing we are all in it together. Hopefully that attitude will prevail and we will emerge stronger for it if we can just keep the disbelieving idiots from infecting the rest of us.

I will be most interested to see if you would accept a “permanent” position there. Hard to re-imagine you as a full time resident anywhere. That would be a very tempting residence.

Thank you Nick for such a great post. I think my stay on Kosrae was less than 30 days but your descriptions of the people and places bring back such memories. You will leave a mark that is remembered and appreciated.

As always, I love reading your blog and getting a vicarious adventure. I wish I were there instead of Shingal, Iraq. We are still shut down, but the government did open the roads between Kurdistan, Shingal, and Baghdad for two days so people, like police, can get their salaries. There is no ATM in Shingal, so I am nearly out of cash.

Sounds like you may have found a home and enlarged a global audience who will be interested in how global climate change plays out on a tiny Pacific Island. Bravo.

Be well and best wishes,

Linda

Wow, Nick. As always, you’ve made a 3-course meal out of what some might call a starvation diet. What makes it really poignant for your readers is that you and we are all in the same boat except for the fact that most of us don’t have access to other people and endeavors. Here, the definition of “doing something” is “staying at home”. It is a great time to go out, though. Walking or biking around DC is fabulous as there is practically no traffic (which normally keeps me from biking at all). Gardening is another great pastime, but the lack of social interaction is stultifying.

In your 8-week “term”, you’ve obviously spread a huge amount of knowledge and understanding — both to the islanders and to your loyal followers. THANK YOU!

Rosemary

p.s. If I ever get stuck on a tiny island, I want it to be with you! 🙂 rbh.

Nice to travel with you while here at home!

Thanks for the great read. I’m a little envious if your life there! It sounds heavenly. I wonder if you’ll miss Clear Lake!

Isn’t it interesting how confines and limits can sometimes open us up to more possibilities? You have indeed made a wonderful feast of a situation others would fight or complain about. Continue to enjoy — and share — your life there.