Senegal − 17 November 2017

Traveling in West Africa requires lots of visas, one for every country, except for Senegal.

Senegal is the only country where an American can arrive by air, land or sea,

present a passport to the immigration official,

and be stamped in at no cost.

You might be asked "How long will you be here?" and/or "Where are you staying?"

Pretty easy.

This is why I figured I'd start my West African adventure here and use Dakar as a base.

Entering Cabo Verde was a breeze, too, because

Cabo Verde is a "visa on arrival" country.

Smile for the camera, pay 25€, get a 30-day stamp in your passport, and you're in.

Yay!

|

|

|

All the other countries in West Africa

(except for Mauritania)

require Americans to have visas in advance of their arrival for land or air entry.

This is why I've spent two weeks running around Dakar getting visas.

Naturally, the embassies are scattered all over the city.

Some are easy to find.

Others are difficult because they're hidden down sandy alleys,

or they've recently changed addresses.

When you've finally found the embassy you're looking for,

be prepared to

stand in queue,

fill out forms (sometimes in quadruplicate),

submit passport-sized photos, vaccination records, airplane tickets and hotel bookings,

and of course,

pay money.

Sometimes a letter of invitation, financial records, or a face-to-face interview is also required.

After doing all that, you'll be told when to come back to collect your visa − assuming you'll be granted one.

(The non-refundable fee you've paid does not guarantee that you'll get a visa.)

|

Mauritania

|

Visa on

arrival

|

$60

|

|

Guinea-Bissau

|

E-visa

|

$75

|

|

Liberia

|

24 hrs

|

$160 &

interview

|

|

Mali

|

3 hrs

|

$45

|

|

Guinea

|

48 hrs

|

$90 &

interview

|

|

Côte d’Ivoire

|

E-visa

|

$86

|

|

The Gambia

|

1 hr

|

$63

|

|

Sierra Leone

|

24 hrs

|

$107 & bank

statement

|

|

Ghana

|

48 hrs

|

$54 &

invitation

|

The secrets to getting visas successfully and in a timely manner are:

- Arrive when the embassy opens in the morning.

- Smile a lot, at everyone.

- Before presenting any documents, ask the staff person if she's having a good day.

- Have all your documents in perfect order and ready to present.

- Don't hurry anything. Act as though you have all day. Enjoy the air conditioning.

- Say thank you frequently − in French, English and Wolof.

Psst ... Here's one more traveler's secret for how to satisfy the annoying visa requirements of

in/out-bound airplane tickets plus hotel reservations.

With priceline.com, you can book an airplane ticket, print it and then cancel it within 24 hours at no cost.

With booking.com, you can book almost any well-known hotel anywhere, print the confirmation letter and then cancel ... again at no cost.

Printed in color, these can be very convincing documents.

In my experience, consulates and immigration officials don't check to see if your bookings are still valid.

If priceline and booking learn about this trick, this secret may not last for long. So, don't tell anyone, okay?

At the end of a week, if you have 3 new visas in your passport, you're doing great.

If you manage to get 4 visas in one week, you're blessed with incredible luck.

I spent almost every morning in an embassy.

In the afternoons, I toured around Dakar.

Dakar on a typical afternoon − temperature 35°C (95°F)

|

Gridlock in Dakar

An average residential neighborhood

Garbage collection by horse cart

|

There are many kinds of transport in Dakar ...

and not enough roads for all of them.

When I had far to go, I took a taxi.

Often the driver had no idea where the embassy was,

so I showed him where to go using maps.me.

Although Dakar is not a pleasant place to walk,

walking was often faster than driving.

I took back streets

and saw much more than I would've seen from the window of a taxi stuck in traffic.

Towering over 1000s of low rise apartments and offices is Dakar's socialist-style African Renaissance monument.

It's the tallest statue in Africa, which is saying something.

|

Crowded public transit in Dakar

The busy Marché Tilène (covered market)

The Monument to the African Renaissance (152m tall)

|

|

There aren't very many tourist attractions, or things to see and do in Dakar.

I visited what was supposed to be Senegal's best museum (Le Musée Théodore Monod) twice.

The first time, on a Wednesday morning, it was closed.

The second time, I searched for 30 minutes to find someone to open it and sell me a ticket.

In spite of being hot, dirty, noisy and chaotic, Dakar has friendly and helpful people.

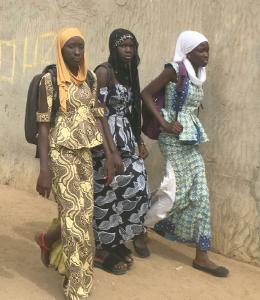

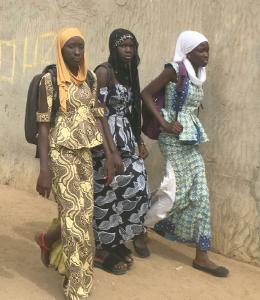

I was impressed by the positive attitudes and colorful fashions of both men and women.

The food was pretty good, too.

The standard quick meal on the street is a chawarama

which is a hot, juicy wrap filled with meat, peppers, onions and French fries.

|

College students

|

Middle-school students in uniform

|

Ladies going shopping

|

|

There are two small islands just offshore from Dakar that are worth a visit.

L'île de Gorée,

just off the southern tip of Dakar,

was used by the Portuguese, Dutch, English and French as a slave holding and trading site.

From the lower level of the Maison des Esclaves (House of Slaves), I got chills as I looked through the infamous "Door to Nowhere."

Through this stone portal, countless West Africans were pushed from their dungeons onto ships waiting to carry them to the New World.

L'île de Gorée, the largest slave trading center on the African coast for 300 years

|

|

Just off the north coast of Dakar lies L'île de N'Gor.

This island is a backpacker and surfer paradise.

Transportation to N'Gor is appropriately funky.

Fishermen with motor boats and guys with piroques ferry people back and forth from the mainland to the island.

There's no schedule.

Be prepared to wade out to the waiting boat.

You might be given a life jacket, but it probably has no ties to hold it on.

But don't worry.

If your over-loaded boat capsizes, you won't have more than a few hundred meters to swim.

One of your fellow passengers with a surfboard might help you.

There are no wheeled vehicles on N'Gor.

No one wears shoes.

In the day, people swim, surf and sun-bathe.

At night, people play drums and dance around the beach bonfires.

|

A pirogue to L'île de N'Gor

|

Black dreadlocks and white dreadlocks on N'Gor

|

I ended my visit to Senegal with two nights on N'Gor.

The fish are fresh.

Life here is slow-paced and relaxed.

There's no internet.

Beer is plentiful,

as are other intoxicants.

N'Gor was the perfect antidote to the traffic, noise and crowds of Dakar.

|

Waiting for sunset and grilled fish

|

A photo of Lake Retba, taken with my iPhone SE

|

30 km east of Dakar is an unusual lake.

Lake Retba is extremely salty.

It's also colored pink by Dunaliella salina bacteria.

(The water looked kinda brown to me.)

Until 2007, Lake Retba was the finish line of the Paris-Dakar Rally.

I think this might be an over-rated tourist attraction.

|

Someone else's photo of Lake Retba, filtered or enhanced?

|

Mauritania − 20 November 2017

Mauritania is 90% desert.

Distances are huge.

Most roads aren't paved.

There's no public transit.

Taxis are unreliable and expensive.

20% of Mauritanians live on less than $1.25/day.

Although Mauritania officially abolished slavery in 1980,

4% of the population are enslaved against their will.

Mauritania is said to have some of Africa's grandest scenery and World Heritage caravan towns.

However, these areas are currently off-limits to visitors for security reasons.

With these facts in mind, I spent two days and three nights in Mauritania −

which turned out to be plenty of time to see Mauritania's capital and the beach.

|

|

|

Getting into Mauritania was interesting.

I flew from Dakar to Nouakchott, Mauritania's capital.

My airline was Mauritania Airlines,

whose Facebook page proudly announces that they've expanded their fleet to five airplanes.

The fact that my plane was only 20% full tells me that Mauritania Airlines probably has enough planes.

On arrival, I was treated to a bowl of grapes while a brightly-robed clerk collected my $60 visa fee and my fingerprints.

At passport control, the uniformed immigration officer went slowly through my passport,

reading carefully the details of my 37 pages of stamps and visas.

While studying my passport,

he asked me three times for the name, address and phone number of my guest house −

even though this information was clearly written on the immigration form in front of him.

By the time he finished reviewing my passport, it was 11pm.

I was the only foreigner remaining in the small, quiet airport.

The immigration officer expressed concern that I might need his help finding a taxi.

Sure enough, when we exited the terminal into the cool desert night,

all the taxis were gone −

including the driver who had been sent by my guest house to meet me.

He had given up and gone home.

The officer pretended to telephone a taxi for me.

Just then, an ancient Toyota pulled up and asked me if I needed a ride into town.

I said "oui" and negotiated a price.

As I got into the taxi,

the immigration officer requested $10 for his help finding "my taxi."

I laughed, made an appropriate remark in French, and drove away in the Toyota.

I expect I'll see more of this sort of behavior in the weeks ahead.

This is Africa.

|

Downtown Nouakchott, Mauritania's capital and largest city

|

Nouakchott is a small, dusty city at the western edge of the Sahara.

The first few times I heard people say the name of this city,

I thought they were clearing their throats.

Nouakchott is home to a third of Mauritania's 4,000,000 residents.

I walked around town for a morning looking for a functional ATM

and photographing people.

|

|

With 4 people per square kilometer,

Mauritania has one of the world's lowest population densities.

Its population is almost equally divided between Moors of Arab-Berber descent and black Africans.

This is a striking cultural combination that's part of Mauritania's appeal,

or so the guidebook says.

|

|

|

In the city market,

the vehicles were donkey carts

and the streets were sand.

Many people covered their faces

− not only for religious reasons −

but out of necessity.

|

|

|

The largest and most impressive building in Nouakchott is not the Grand Mosque or Parliament.

It's the new American embassy.

I gathered from the height and thickness of the walls around this fortress

that the US is taking Mauritania's political situation seriously and

wants to ensure that another "Benghazi" does not occur here.

While I was taking this snapshot, I was probably photographed by at least a dozen American security cameras.

|

The new American embassy in Nouakchott, Mauritania

|

Fishing boats parked on the beach

|

Unloading the morning's catch

|

Besides its busy city market,

Nouakchott's other colorful attraction is the daily fish haul.

With no docks on the beach,

fishermen unload their catch onto the sand.

Workers gather the fish, wash them and then sell them under thatched shanties.

In the bright desert sun, this is a sight to see ... and smell.

|

A pile of fresh sharks

|

|

Where the dunes of the Sahara spill down to the Atlantic Ocean,

Mauritania has about 400 kilometers of wide, pristine beaches − which are mostly deserted.

Enterprising locals have erected tents for day and night use.

Their cook-houses produce delicious fish dishes.

I spent a night in one of the semi-permanent tents here

and enjoyed falling asleep to the sound of the surf.

From this beach, I witnessed the most brilliant green flash I've ever seen.

The Leonid meteor shower was pretty good, too.

Les Sultanes "beach resort" on a Saturday afternoon

|

Mali − 22 November 2017

From Mauritania, I flew to Mali for an equally short visit. I cut my visit short because ...

- The US State Department, as well as my Lonely Planet guide, says don't come here.

Tourism is restricted. Foreigners aren't allowed to travel outside the capital.

- After the Tuareg rebellion in 2012,

Islamic militants

moved in,

relocated the Tuaregs,

installed Sharia law,

and destroyed many of the historic sites that I'd hoped to see in Gao and Timbuktu.

Nevertheless, I'm glad I came to Mali.

|

|

The life-giving Niger River at the edge of the Sahara

|

I took the photo to the left as my Mauritania Airlines flight approached the airport in Bamako, Mali.

This is the big, shallow, slow-moving Niger River.

Thanks to this river, southern Mali is green − unlike Mauritania.

The Niger River creates an inland floodplain that supports agriculture.

Consequently, the southern half of Mali is a gigantic oasis at the edge of the Sahara.

In centuries past, cities like Timbuktu and Gao prospered because

they were well-watered trading centers on the trans-African caravan routes.

Today, Mali is still an important trading hub in west Africa.

Bamako, Mali's capital (population 1.8 million), straddles the Niger.

This bustling city was estimated to be the fastest growing city in Africa in 2006.

|

Bamako's city markets fill many streets

|

The center of Bamako is a huge street market.

The sun is intense.

Merchants shade themselves and their wares with umbrellas.

|

She sings as she sells silver

|

Traditional weaving method

|

Poverty is prevalent throughout West Africa.

In Bamako, people make money by producing and selling whatever they can.

They use traditional methods with minimal modern technology.

Fortunately, there are many markets in Bamako where these goods can be sold.

Mali is the 2nd largest producer of cotton in Africa, after Egypt.

Weaving beautiful geometric fabrics has a long tradition in Mali.

People are very skilled at using looms.

In the video to the left,

the man's hands and feet really did move that fast.

Mali also has rich musical traditions.

Click here for a modern example.

Some folks believe that American blues originated with the Malian slaves who worked on US plantations.

I tried to find a good music venue in Bamako, but I think those clubs are currently closed.

|

|

Bamako has a beautiful

National Museum

which presents information on Mali's art, archaeology, history and traditions.

Here, I learned about Timbuktu, Gao and the Great Mosque of Djenné.

Since no one can go to these places now,

I had to be satisfied with seeing the scale models in the museum's park.

French is an official language throughout West Africa.

I speak French fairly well.

Yet I barely understood the French that was spoken in Senegal and Mauritania.

Surprise, surprise!

The people of Bamako speak very clear French.

I could understand everyone.

Furthermore, the baguettes are excellent.

Upscale restaurants in Bamako serve good wines.

I stayed in a hotel

(Le Loft Hotel)

that felt like Paris in the 1970's.

In some ways, Bamako feels as though it's still a French colony.

|

A scale model of the Great Mosque of Djenné

|

Pollution, garbage and sewage flow through the city

|

Bamako is a city of extremes.

The wealthy are very comfortable.

The poor struggle to survive.

|

The French café inside Le Loft Hotel

|

|

In coming to Mali, I ignored the U.S. state department's travel advisory to stay away.

In walking around Bamako, I was aware of armed soldiers stationed throughout the city.

Hotels and restaurants frequented by foreigners were guarded.

To enter my hotel or the fine restaurant down the street,

I was wanded by a guard who checked my bags or parcels.

After verifying that I wasn't carrying anything dangerous,

I was buzzed in through a steel door.

A second steel door, controlled remotely, was then unlocked to allow entry.

Airport security was equally strict.

I didn't meet any tourists or Americans in Bamako.

At a pizza place near my hotel,

I shared a beer with Brits, South Africans and Frenchmen

working in Mali to collect unauthorized weapons and explosives.

Although I appreciated the attention given to my safety in Bamako,

my biggest risk was probably

falling through a hole in the sidewalk

or being run over by a speeding motorcycle.

|

|

The Gambia − 30 November 2017

I spent the past week in The Gambia,

a country I first learned about while watching

Roots

on TV back in the 1970's.

Now finally, I get to see what's here:

Friendly people, lush jungles, and a big river.

This is also the first country on my West Africa journey where everyone speaks English.

Yay!

|

|

Banjul (pop. 38,000) is Africa's least populated capital city

|

The Gambia is the smallest country in Africa

− about the size of Delaware and Rhode Island combined.

It consists of the Gambia River and its north and south banks.

The capital, Banjul, is a dusty village.

The Gambia was a British colony from 1783 until its independence in 1965.

Its historic significance is that about 3,000,000 slaves were taken from this region

to the Americas.

Wow!

Today, a third of Gambians live below the international poverty line of $1.25/day,

surviving on farming and fishing.

Tourism and beach resorts help sustain the country's economy.

|

A Gambian gelli-gelli (bush taxi)

|

One of my first challenges in coming to any new country is figuring out how to get around.

Gambian villages are spread out and the sites I wanted to see are far apart.

Gambian taxis are unreliable and they over-charge tourists.

Walking isn't practical.

I learned quickly that most Gambians travel by gelli-gelli (bush taxi).

Gelli-gellis are cheap − about a penny per kilometer.

They're sometimes very slow − if they drop off and pick up many passengers along the route.

They're crowded − these 7 passengers mini-vans often pack 14 passengers inside,

with luggage and teenage boys on the roof.

Nevertheless, Gelli-gellis seem to be an efficient way to move people from place to place.

The driver can focus on his driving

because he has a young assistant who collects the fares and calls out the destinations.

Although they have fairly fixed routes, gelli-gellis run when and where they're needed.

On busy routes, I never had to wait more than two minutes for a ride.

The best thing about gelli-gellis is that they're very sociable.

I met lovely people on every ride.

|

|

The north and south halves of The Gambia are divided by a wide river which has no bridges across it.

I wanted to visit the museum and slave trading house made famous by Alex Haley's

Roots.

These sites are on the other side of the river, so I had to take a ferry. Cost: 50 cents.

|

The ferry across the wide Gambia River

|

|

The crowds disembarking from the ferry

|

French colonial trading house, 1681-1857

|

Shipping records estimate that 10 to 15 million slaves were taken from West Africa to the Americas between 1650 and 1860.

What I didn't realize until I visited the museum here

is that a third of these slaves went to Brazil to work in mines.

Mine work was generally a death sentence because working conditions were harsh and dangerous.

Another third of the slaves went to the Caribbean.

Alex Haley is a name known to almost everyone in The Gambia.

His book put The Gambia on the map, and is the reason why lots of people from Europe and America visit this country.

|

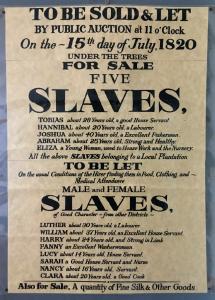

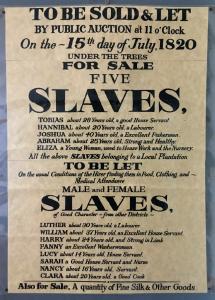

Slaves for sale

|

|

The Gambia River creates a huge salt water estuary system

full of mangrove swamps.

You can − and should − take a boat trip through some of these natural canal systems.

There are few roads, and a boat is the only way to reach these areas.

This delta is an undeveloped part of The Gambia.

The birds and wildlife are amazing.

|

Tidal estuaries and mangrove swamps

|

Egrets nesting for the evening

|

Africa's west coast is on a north-south migratory route.

Many birds flock here to nest and feed in the mangroves.

|

Nile monitor (Varanus niloticus)

|

|

The Gambia has many other native species,

especially reptiles.

The Nile Monitor is a relative of the Komodo Dragon of Indonesia.

These lizards are big enough to be aggressive.

In my experience, they are not afraid of humans.

They also swim very well.

In The Gambian jungles, you might spot one of Africa's most dangerous snakes:

The Green Mamba, whose victims usually die within 30 minutes.

Most tourists who come to The Gambia

stay at hotels on the beach.

They spend their time at the up-scale restaurants and bars.

Not me.

I headed inland to see the "real" Gambia.

I rode gelli-gellis down sandy roads through the river delta

until I came to a village called Kumbaya.

Yes, that's its name: Kumbaya, just like the song we used to sing at summer camp.

|

Green Mamba (Dendroaspis viridis)

|

Three generations relaxing at home

Pounding to separate the rice from the hulls

|

The villages of Kumbaya, Kabuneh and Galowya were selected to be part of an international art project called

Wide Open Walls,

through which European art students collaborated with local artists to

decorate people's homes with imaginative and colorful images and graffiti.

As I walked through the villages taking pictures of the artwork,

I got used to being followed by flocks of children, and

being called Toubob.

This isn't a derogatory term.

It's just the West African word for a European.

I stumbled upon the rustic Wunderland Lodge,

with bungalows by the water,

the sound of birds all day and night,

and no paved roads for miles.

It has wifi, cold beer, great food and is run by a very hospitable couple shown below.

I spent three nights here and could have stayed here for a month.

Highly recommended!

|

The children of Kumbaya

Fish and rice for lunch

|

The tranquil and relaxing Wunderland Lodge

|

My hosts, Kumba and Lamin

|

|

From The Gambia, I'll continue south to Guinea-Bissau.

|

|

Guinea-Bissau − 5 December 2017

I left The Gambia on a big GTSC bus,

bouncing through southern Senegal into Guinea-Bissau.

The roads were full of potholes.

The A/C didn't work.

There were at least a dozen checkpoints where police checked our passports and/or IDs.

We stopped often to pick up and drop off passengers.

It took 12 hours to go 250 km.

Still, it was the smoothest and fastest African bus ride I've had so far.

|

|

|

On this bus ride, I got a good illustration of how business is conducted in West Africa.

As we rolled through our final border crossing,

in the no-man's land between Senegal and Guinea-Bissau,

one of our passengers − a Gambian in his mid-20s −

announced that he didn't have a passport or an ID card,

and that the immigration police in Guinea-Bissau probably weren't going to let him cross the border.

The bus stopped.

My excited fellow passengers were impressed and amazed that this young man had slipped through the previous

ID checks and international borders without any documentation.

Everyone brain-stormed about how to solve the young man's problem,

while vendors came on-board to sell cashews and change money.

It was decided that our bus driver and two of the men on the bus would accompany the young man back to the Senegalese border

to sort out a solution.

The rest of the passengers remained on the bus eating cashews in the sweltering heat.

Half an hour later, our negotiating party returned successful.

The young man was smiling as he waved a piece of paper covered with enough stamps and signatures to allow his entry into Guinea-Bissau.

No one complained about the delay.

We arrived in Bissau before dark, which was good enough.

This is how things get done in Africa.

|

The center of Bissau: The Place d'Independance and the Presidential Palace

|

Surprise, surprise! Bissau looks like a city.

It has

paved streets,

traffic lights

and

a central plaza.

There's a hint of European styling to the cafés and restaurants.

This is a former Portuguese colony,

so everyone speaks Creole Portuguese here, just as they do in Cabo Verde.

But unlike Cabo Verde,

there's almost no tourism here.

Guinea-Bissau spent the 60's and 70's in a long and bloody war of liberation from Portugal.

The 80's was a time of coups and experiments in socialism.

The 90's saw growing corruption, national strikes and civil war.

Extreme poverty motivated farmers to replace cashews with cocaine.

In 2009, the president was assassinated.

Since May 2014, Guinea-Bissau has had five prime ministers.

A year ago, the government was dissolved.

On the bright side,

Lonely Planet says that attacks and coup attempts rarely wound civilians or visitors.

|

|

Within the first two hours of my arrival in Bissau, I was asked three times:

"Why did you come here?"

I travel to learn about people and places that I don't know about.

You can't know what someplace is like unless you go there.

What's written about a country often doesn't tell the whole story − or even half of it.

So, I came to Guinea-Bissau to see for myself what's really here.

It turns out that Guinea-Bissau is a pretty interesting place.

The people are friendly, easy-going and never aggressive.

Bissau is a bit run-down, but it's got potential.

Although a lot of the country consists of swamps, subsistence farms and poor villages,

the offshore islands are amazing and wonderful.

Guinea-Bissau feels like a new frontier.

I met a few European entrepreneurs who have come here to start new lives and new businesses.

The government is making an effort to encourage tourism by offering an

on-line e-visa.

Foreigners can buy a 5-year residency permit

by filling out a one-page application and paying 100 euros.

There are direct flights between Bissau from Lisbon.

|

An old colonial building in Bissau Velho (Old Bissau)

|

|

For me, the place to go in Guinea-Bissau is the Bijagós Archipelago.

This is a sunken river delta

at the mouth of the Gêba River.

There are 87 forested islands here.

Except for 20 settlements − which are home to a few thousand people −

the islands are mostly untouched wilderness.

Millions of birds nest in vast mangroves and wetlands.

The clear, clean waters are inhabited by dolphins, salt-water hippos, manatees and sea turtles.

To get to the Bijagós Archipelago,

I took the Consulmar Ferry from Bissau to Bubaque.

The ferry was seriously overloaded.

There were only a handful of life-jackets for about 250 passengers.

(If the ferry had capsized, I would only have had to swim a couple of miles to an island.)

At low tide, my ferry ran aground twice.

But we managed to cover the 60 kms to Bubaque in 4 hours.

Yay!

|

|

From Bubaque, I took a motorized canoe to the Afrikan Ecolodge

on Angurman Island.

I had the island to myself for four days except for ...

- François who cooks and manages his Ecolodge

- A native family who clean and maintain François's bungalows

- Four French tourists who came ashore for a picnic

- Three young doctors from Lisbon who came for one night

- Some fisherman who sleep on one of the beaches

|

Passengers boarding the ferry to Bubaque

|

A beach on Angurman Island − my bungalow in the background

|

The baobab tree in front of my bungalow

|

The Afrikan Ecolodge

is a tropical paradise.

There are almost no mosquitoes and not a single stingray.

François is a fabulous chef.

The gigantic Kapok tree

in the middle of the camp is like something out of the movie Avatar.

I had to pinch myself and ask "Am I making this place up?"

One of the reasons I travel is to find destinations like this.

I might come back here some day.

|

The shaded spot where I ate my meals

|

Fishermen praying for a good catch and a safe return from the sea

|

There are 27 ethnic groups scattered through the jungles and islands of Guinea-Bissau.

Of these people, 45% are Muslim, 10% are Christian and 100% are Animist.

I had a rare invitation to join some fishermen one morning for an Animist ceremony under the baobab trees.

Inside the thatched hut was a fetish object that no one was allowed to see.

Outside, there was much chanting and praying to a large, round stone wrapped in a shawl.

The ceremony was accompanied by grilled fish and cheap rum.

When the bottle was passed around a second time,

each man took a swallow and spat the remainder (of the rum) onto the large, round stone.

As with fisherman rites worldwide, we were praying for a good fishing season and safety at sea.

I prayed for a safe return to Bissau.

|

|

In the past month, I've met many European tourists.

In Guinea-Bissau, most of the visitors are Portuguese and French.

I have yet to meet another American.

François tells me that the only other American who ever visited his Ecolodge was a guy from Lonely Planet.

This part of the world is unknown to Americans,

which makes my journey feels like an exploration of undiscovered places.

It's an exhilarating feeling.

From Bissau, I'll continue overland into Guinea,

also known as French Guinea or Guinea-Conakry.

|

|

Guinea − 10 December 2017

I spent five days passing through Guinea −

not to be confused with Guinea-Bissau, formerly Portuguese Guinea, where I was last week −

or Equatorial Guinea, formerly Spanish Guinea, which is someplace I won't get to this year −

or the island of New Guinea, which is north of Australia, and nowhere near Africa.

Have you ever wondered why so many places are named Guinea?

The word Guinea comes from the 15th century Portuguese word Guiné,

meaning "black man."

Think about it.

|

|

|

Guinea was a French colony.

In 1958, Charles de Gaulle offered all of France's colonies the opportunity to be totally free and independent,

or to remain supported by and dependent upon France.

Guinea was the only French colony to opt for independence.

Under the leadership of President

Ahmed Sékou Touré,

Guinea voted overwhelmingly "to be poor and free, rather than rich and enslaved."

I have the sense that Guineans are happy and proud to be free,

even if it means being poor.

Guinea remains poor

even though it's the world's second largest producer of bauxite,

and has deposits of diamonds and gold.

The

Ebola outbreak of 2014

had a lot to do with this.

Until the country was declared free of Ebola in 2016, this country saw zero tourists or international commerce.

Enough history.

|

One of my many drivers

|

For travelers, the biggest challenge in Guinea is simply getting from place to place.

The roads are terrible.

The transport is designed to move as many people as possible as cheaply as possible,

with the key word here being cheap.

|

There are 11 adults and 2 children inside this car.

|

|

The most common transport in Guinea is the

Renault 21 Nevada,

a seven-seater hatchback station wagon.

In 1987, this car won "Car of the Year" and "Best Family Saloon."

You won't see many of these antiques in France these days because they're all here in Guinea ...

where instead of being seven-seaters,

they're now 11-seaters, with luggage, goats, chickens and extra passengers on the roof.

The first time I went to a shared taxi depot,

the ticket handler suggested that I pay for two seats.

At the time, I didn't know what this meant, but was very glad to have bought two seats.

This meant that I rode shotgun next to the driver, in a seat all to myself.

(Normally, the front passenger seat is occupied by two people.)

I looked back to see how my fellow passengers were doing.

There were 8 adults packed into the two back seats, with 3 babies on laps.

We then drove

360 kilometers

in 10 hours

in 35°C (95°F) heat

on bone-jarring dirt and gravel roads.

I was really glad to have a window seat and a seat belt.

I'll never complain about cramped seating on commercial airplanes again!

Many tourists avoid the shared taxis by hiring a private tour guide and a cushy, air-conditioned 4x4.

Had I done that, I wouldn't have met all the wonderful people I met along the way.

After a few days in Guinea, I figured out how to enjoy a shared taxi ride:

- Arrive at the taxi depot at dawn.

That's when the taxis fill quickest and the wait is shortest.

- Buy two seats and make yourself comfortable in the front passenger seat.

This will mean paying $20 − instead of $10 − for a journey of a few hundred kilometers.

- Introduce yourself to the driver.

He'll be pleased to be sharing the front of the car with only one passenger.

- Buy snacks from the vendors who come to your window before departure.

Plan on spending a dollar or two.

- When the taxi pulls out of the depot,

distribute snacks to the driver and to the passengers crammed into the back of the car.

You now have nine new friends.

- Join your new friends at the lunch stop. They'll show you where and what to eat.

- When you come to a Guinean checkpoint, just smile.

If a policeman or a soldier starts asking you questions,

your fellow passengers will vouch for you − loudly, if necessary.

The officer will return your passport and wave you through.

- At your final destination, your fellow passengers will ensure that you find your way to wherever you're going next.

You might even exchange a few email addresses with the wonderful people you've spent the day with.

|

Miles of dusty, rutted roads full of vehicles

|

Traffic gridlock in Conakry, Guinea's capital

|

|

North and central Guinea is 1000-1500 meters above sea level.

It's cooler up there.

The air is clean and fresh.

The scenery is nice.

There are good places for hikes.

|

Round houses and steep cliffs in northern Guinea

|

Oranges, papayas and pineapples for sale − fresh and delicious!

|

Beans and rice for lunch

|

What I'll remember most about Guinea is its people.

- When I asked for directions,

Guineans often walked me to where I wanted to go.

If I offered to pay them for their help, my money would be refused.

- When I shopped at markets, I was charged the same prices as the locals.

- On one occasion, I accidentally overpaid a shared taxi driver.

He promptly gave me back my overpayment.

- Contrary to what the guidebooks say,

the police were polite and friendly, and never demanded a bribe.

These sorts of things don't happen in most of the countries I've been to.

|

The chef and her daughter

|

|

Guinea's capital city, Conakry, is on a polluted and crowded peninsula.

The traffic is terrible.

There's garbage everywhere.

Conakry reminds me of Kolkata, India.

Conakry is full of life.

The sidewalks overflow with people buying and selling.

At low tide, kids play soccer on the beach

because there's no place else in the city with a large open space that's garbage-free.

Loud African music plays from noon until 3am.

For anyone looking to do something positive and adventurous,

Guinea's highland interior would be an attractive place to do volunteer work.

The weather is cool(er).

The cost of living is low.

The Guineans are friendly and honest.

They could use some help.

Anything you could do to improve their lives would be appreciated.

|

Soccer games at low tide in Conakry

|

|

|

Civil wars in Sierra Leone and Liberia from 1989 to 2003 killed about a million people,

and displaced two million more.

Then in 2014, just as these countries were beginning to recover,

the West African Ebola virus killed another 10,000 and closed their borders for a couple of years.

In spite of these disasters,

I found the people here to be some of the most friendly and joyous people I've met along my journey so far.

Maybe it's because the survivors are thankful to be alive.

|

Sierra Leone − 14 December 2017

My story begins at the Sierra Leone embassy in Dakar.

When I applied for my Sierra Leone visa,

Mr. Kaikai, the chief of the embassy, wanted to chat with me.

He was curious as to why I wanted to visit his country.

We had a warm and sociable conversation,

at the end of which Mr. Kaikai urged me to stay at his guest house in Freetown

which Mrs. Kaikai manages in his absence.

He gave me a note introducing me to Mrs. Kaikai − with a generous discount on my lodging.

I left the embassy thinking how convenient it was to get a visa and a place to stay.

|

|

My first view of the highway system in Sierra Leone

|

I took a bush taxi from Guinea to Sierra Leone.

As expected, the roads were terrible in Guinea.

The potholes were as big as bathtubs.

Suddenly, on crossing into Sierra Leone,

we came to a brand-new divided highway with toll booths.

I thought I was dreaming.

I haven't seen roads like this since California.

It didn't take long to spot the Chinese construction equipment and supervisors.

The Chinese built this road to extract the iron and hardwoods from Sierra Leone's back country.

The tolls collected on this highway go to China, not to Sierra Leone.

This is typical 21st century colonization and exploitation.

I've seen this sort of thing all over Africa.

Still, I was thankful for a paved road.

|

|

On arrival in Freetown,

I was warmly welcomed by Mrs. Kaikai.

I felt like I was at home,

complete with Creole (Krio) home cooking.

If you're ever in Freetown,

try the

Simple Goal Guest House,

+232-76-271224, emkay.simplegoal@gmail.com.

Sierra Leone has a lot in common with South Carolina:

- Sierra Leone and South Carolina are about the same size.

- They're hot and humid.

- Rice grows well in both places.

- They were both British colonies.

- Most of the slaves in South Carolina (and Georgia) came from Sierra Leone.

- Many freed slaves returned from America to Sierra Leone.

So, it's no surprise that Sierra Leone feels like the Deep South.

The cuisine, the architecture, the music and the people are similar − and even related.

I spent a couple of days wandering around Freetown learning American history.

Freetown has the largest natural deep-water harbor on the continent of Africa.

This is why Britain was so keen on capturing and holding this part of Africa.

At the top of Freetown's harbor is Bunce Island,

located as far upriver as big ships can sail,

while being easy access for canoes and riverboats coming downriver.

The British built a fort and slave trading center on Bunce Island.

Most of America's slaves were shipped from here.

During the 1770's,

Bunce Island was owned by Richard Oswald.

Meanwhile,

on the other side of the Atlantic in South Carolina,

Mr. Henry Laurens received the British slave ships from Sierra Leone,

auctioned the captives to local rice plantations,

and sent the proceeds to London.

|

Grilled fish, plantains, veggies and spicy Creole sauce

In 1777,

Laurens was elected President of the Continental Congress.

After the Revolutionary war,

Laurens helped negotiate the U.S. independence under the Treaty of Paris.

The British negotiator, sitting across the table from Laurens,

was none other than Richard Oswald.

Thus, American independence was negotiated between a British slave dealer

and his South Carolinian business agent.

Here's another historical tidbit:

In the early days of Bunce Island,

the British branded slaves with the acronym "RACE"

which stood for Royal African Company of England.

Could this be how the word "race" was introduced into America?

|

Morning market on Kissy Street in Freetown

|

Kekes are small, fast, cheap and comfortable.

|

The Cotton Tree is the historic symbol of Freetown.

|

Bunce Island and Freetown are arguably the most important historic sites in Africa for the United States.

Freetown was established as a place for slaves to be free.

As the story goes,

when the first slaves arrived here in 1787,

they walked up to a giant cotton tree just above the shore and held a thanksgiving service there for their deliverance to a free land.

The tree still stands today.

Seeing this tree gave me goosebumps.

|

The clock tower marks the center of town.

|

Tie-dyed and batiked fabrics on sale everywhere

|

Something I noticed in Sierra Leone, and later in Liberia,

was groups of people dressed in the same fabric.

This is a tradition called eshowbi.

It lets everyone doing something together show that they're part of the same

organization,

group

or

family.

Eshowbi will be important in the next part of this adventure.

|

Mothers in uniform (eshowbi) for a school event

|

Crossing the Moa River near Jaiwulo

|

To get from Freetown, Sierra Leone to Monrovia, Liberia, I decided to go overland.

This is a jungle route with 575 km of potholes, mud and water.

(The Chinese haven't paved these roads yet.)

I took a car, a bus, a motorcycle, a LandCruiser, a ferry, another motorcycle and a taxi.

Some people have done this journey in a day.

In my case, this was a two-day journey because of flooded roads, a border closure and a flat tire ...

... and it was lots of fun!

|

Half of my traveling companions were a wedding party en route from Freetown to Monrovia to see their sister get married.

Like everyone else I met in Sierra Leone, they were friendly and hospitable.

By the time we'd shared five meals,

pushed our vehicle through the mud,

waited by the river for the ferry,

and camped overnight at the border,

we were all good friends.

When they presented me with my eshowbi shirt, I was part of the family.

NB: This sort of thing doesn't happen when you take an airplane.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

It's amazing to think that these joyous people recently survived two civil wars and the Ebola epidemic.

|

|

Ghana − 23 December 2017

Ghana and Côte d'Ivoire could be described as "Africa Lite".

The roads are paved.

Public transit − including shared taxis and mini-vans − are not overloaded.

The windshields are not cracked

and

seat belts are provided.

Intercity buses run on time and have assigned seats.

The phone network is 3G and sometimes 4G.

Hotels have hot showers and fast wifi.

The beer is always cold.

This is a welcome relief from the past month of roughing it through The Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia.

|

|

Donations to the orphanage

|

In Ghana, I joined an NGO named

People To People.

Dwight Eisenhower founded this organization

to promote international friendship

through humanitarian projects.

Our first project was to deliver food and supplies to a children's home in Kumasi,

in rural Ghana.

Our second project was to provide a library for a middle school in nearby Aduman village.

|

Students at Aduman Secondary School

|

|

The school visit was particularly entertaining.

Although classes were suspended for Christmas vacation,

700 students returned to their school and spent a whole morning

marching, singing, dancing and drumming for People To People

to say thanks for providing books, desks and chairs for their new library.

I try to avoid being a tourist.

By donating my time and money to good causes as I travel,

I meet great people,

get to know cultures,

and

visit beautiful places that aren't in the guide books.

Nevertheless, some tourism is necessary to seeing and learning about a place.

Ghana has two well-preserved and infamous slave castles which I had to see.

|

A traditional Ashanti dance at the school in Aduman

|

|

Cape Coast Castle

is one of about 40 slave storage and shipping centers built along the Gulf of Guinea.

The dungeons, the shackles, and the Gate of No Return

are preserved to remind us of the millions of people imprisoned here.

About half of them died prior to transport to the Americas.

|

The slave castle in Cape Coast

|

Fishing boats outside Cape Coast Castle

|

Portugal built a fortress at

Elmina in 1482,

making it the oldest European building south of the Sahara.

Though first established as a trading post,

this is where the barbaric

Atlantic slave trade began.

|

Elmina's slave castle and fishing harbor

|

|

These slave castles are powerful sites to visit.

They're not for the squeamish, but essential for understanding mankind's tragic past.

These slave castles rate right up there with

Auschwitz,

the Killing Fields,

the boneyards of Rwanda,

Armenia's Genocide memorial

and

Hiroshima's Peace Park.

Some day, maybe we'll learn how to prevent these sorts of tragedies from occurring.

|

|

The Sofitel was close to something I wanted to see in Côte d'Ivoire:

La Cathédrale Saint-Paul d'Abidjan.

Designed by Italian architect Aldo Spiritom and completed in 1985, St Paul's Cathedral is a bold and innovative modern cathedral.

The design is intended to look like Jesus lifting and pulling the cathedral forward.

(Yes, that's a gigantic, stylized statue of Jesus in the photo to the left.)

The seating and standing capacity is about 5000.

The stained glass windows feature elephants and scenes from life in Africa.

I knew the music would be good at the cathedral on Christmas morning,

but I didn't know how good.

I went to the 8:00am mass, and stayed for the 9:30am and the 11:00am services

just to hear the choirs − all three of them.

There was a different choir for each service.

For my Christmas dinner,

I could have had goose or turkey with all the trimmings at the Sofitel.

But what's the point of traveling to distant lands if you're just going to live the way you do back home?

I ventured out to dine with the locals at a maquis (rustic, open-air restaurant).

I ate chicken smothered in peppers and onions,

served on a wooden tray and

with a hot sauce that would've melted the icicles on Santa's sleigh.

In all, I spent about 48 hours in Côte d'Ivoire.

I know that this isn't enough time to really get to know a country.

My impression is that Côte d'Ivoire is the French-speaking version of Ghana,

with wider roads and fancier hotels.

I have lots more of west Africa still to see,

so I can't linger too long in one place.

Next stop: Burkina Faso.

|

Click on the picture to hear the choir sing.

|

My Christmas dinner

|

|

Burkina Faso − 30 December 2017

This little land-locked country has

friendly people,

a colorful history,

and

more than 60 tribes and languages.

This is also a very hot, dry and dusty place.

One of the first things I noticed is red dust everywhere.

Some folks say that it's red because of all the blood that's been spilled here.

A geologist will tell you that it's because of all the iron in the rocks and the soil.

Archaeologists have verified that

the African Iron Age

started here about 2500 BC

when the inhabitants learned how to smelt iron.

And that's what put this little country on the map and on the trans-Saharan caravan routes.

|

|

Street art in Ouagadougou

|

The capital of Burkina Faso is named Ouagadougou,

pronounced Wa-ga-doo-goo.

This sounds like a name my son made up when he was about 3 years old.

Most people just call it Ouaga (Wa-ga) for short.

|

Red dust everywhere

|

The bizarre Monument to National Heroes

|

I spent three days in this little city

strolling through markets,

admiring handicrafts,

eating local food,

and listening to traditional music.

Lonely Planet says this is the safest city in west Africa.

I'd agree.

It's very mellow here.

No one hassled me.

One morning, I attended the weekly Moro Naba Ceremony

at which the emperor of the Mossi tribe appears before his chiefs and his subjects

to give them his blessings and to promise that he won't go to war this week.

|

Hijabs for sale outside the mosque

|

Mossi tribal chiefs attending the Moro Naba Ceremony

|

Taking live chickens and goats to market

|

Ministry of Environment, Green Economy

and Climate Change

|

Near my art-themed guest house,

I spotted the Ministry of Environment, Green Economy and Climate Change.

I was impressed that an impoverished country like Burkina Faso takes climate change seriously.

They have to.

The northern third of Burkina Faso is the Sahara desert.

The central region is a dry plateau of hardy trees and bushes,

suitable for grazing a few goats and sheep.

Only the southern 13% of Burkina Faso gets enough rain to be arable.

The Sahara is advancing south 10 kilometers every year.

If this advance continues,

Burkina Faso will have no farms 30 years from now.

The Burkinabé people are hospitable and sociable,

and they were especially friendly to me.

Due to a funny linguistic coincidence,

everyone in Ouaga seemed to know my name.

I heard it spoken − even shouted − frequently around town.

I received a warm reception every time I showed my passport.

When dealing with customs and immigration,

there were big smiles and enthusiastic handshakes.

Towards the end of my visit, someone finally told me what was going on:

ZOA just happens to be the Mossi word for "friend!"

|

Niger − 2 January 2018

Getting into Niger involved an only-in-Africa bureaucratic adventure:

- In Ouaga, I paid $44 for a

Visa Entente

which I'd read was valid for Burkina Faso, Togo, Benin and Niger.

- Handing me my visa, the officer in Ouaga said my Visa Entente was valid everywhere except Niger.

- I applied for a Nigerien visa, but was told that I didn't need a visa because I had a Visa Entente.

- At the Ouaga airport, I was allowed to board my plane to Niger with my Visa Entente.

- In Niger, immigration assured me that my Visa Entente was valid ... but that confirmation was needed.

- When the immigration boss arrived, he explained that my Visa Entente was not valid.

- From the airport, I was driven on the back of a motorcycle to La Direction de Surveillance Territoriale.

- Two hours later, my passport was stamped with a Nigerien visa good for 30 days in exchange for $36.

This is how business gets done in Africa.

|

|

View of the Niger River from the terrace of The Grand Hotel

|

Niamey, Niger's capital, would not exist if it weren't for the Niger River.

This is the source of water and life.

The Sahara surrounds the capital.

It's always dry here, especially in the winter months when

the Harmattan blows down from the Sahara.

In winter, there are no clouds in the sky in Niger.

But the skies aren't blue −

they're brown, gray or yellow depending on which way the wind is blowing.

I enjoyed a grand view of the river from the terrace of

The Grand Hotel.

This was my oasis from the hot, dry, dusty city.

It was also an excellent place from which to watch New Year's fireworks.

|

Taking woven mats to market

|

Le Grand Marché, one of west Africa's biggest markets

|

|

In contrast to Ouaga,

Niamey didn't feel particularly safe.

There's extreme poverty here.

There are many crippled and disfigured people in the streets,

as well as many beggars.

Niger has the highest birth rate in the world.

In 2015 it was estimated that women have a staggering average of seven children each.

Walking around town,

I got strange reactions from people.

People didn't really know how to react to me.

There are no westerners in the streets.

The few ex-pats who live and work here travel in big cars or 4x4s with tinted windows,

and spend their time indoors.

I didn't leave my hotel at night,

which was fine with me because the gardens were lovely.

Even at the mosque, I got a cold reception.

The guards didn't want me to come in unless I paid them some money.

|

Le Grand Mosque

|

Dust storms are common in January and February.

|

Added to the poverty of Niger is the dust.

The summer months bring occasional rain to keep down the dust.

During the winter months the

Harmattan blows dust and sand down from the Sahara.

I encountered one dust storm and was able to take refuge in a shop that had doors and windows.

Every afternoon in Niamey, I returned to my room to rinse the dust out of my clothes.

Due to security problems,

almost every Western government advises against all travel to virtually the entire country.

The only exception is for travel to Niamey and a narrow band across the south.

Niger is the only west African country that I don't feel the need to revisit.

You can probably take Niger off your bucket list.

From here, I'll fly south to Benin,

where I can expect to have hot, humid weather.

But at least it won't be dusty.

|

|

Benin − 5 January 2018

After a week in the dry, dusty Sahel of Burkina Faso and Niger,

I was glad to return to the humid tropics of Benin and Togo

with their

lush jungles,

coastal lagoons

and

beautiful beaches.

Benin and Togo are famous for Voodoo.

About half the citizens of these two countries follow Voodoo practices,

which they do in addition to praying at a mosque on Friday or attending mass at a church on Sunday.

In Benin, Voodoo is officially recognized as a religion.

|

|

Community center decorated with Voodoo symbols and spirits

|

Voodoo cosmology centers around spirits that govern the Earth, nature and human society.

These spirits are similar to our saints or angels,

but they take the form of animals, streams, trees and rocks.

In Voodoo, the spirits of the dead live side by side with the world of the living.

So, don't forget to bake a birthday cake for your great-grandmother.

|

Pythons are household pets in Benin.

|

Voodoo fetish market

|

The village of Ouidah is the Voodoo capital of Benin.

Being naturally drawn to the bizarre, I had to spend a few days here,

even though it was a little creepy to walk around a town full of snakes, bats, skulls, weird statues and scary murals.

As my guide explained, all of creation contains the power of the divine.

Herbal medicines work because they're created by nature.

Mundane objects, like rocks and feathers, have spiritual powers.

Talismans (aka "fetishes") are objects such as statues or dried animal or human parts

which have healing and rejuvenating properties.

Voodoo picks up where Christianity leaves off.

Saints aren't limited to human beings.

In Ouidah, the Temple of Pythons and the Basilica face each other across the town square.

Holy snakes!

|

My Voodoo guide

|

Friendly kids posing for their photo

|

In addition to learning about Voodoo,

Benin is worth visiting for ...

- Friendly people:

People throughout west Africa have consistently greeted me with a smile and a handshake.

In Benin, I was pleased that people would also let me take their photos and help them cook.

- Interesting cuisine:

In southern Benin, the most common ingredient is corn,

often used to prepare dough which is served with spicy peanut- or tomato-based sauces.

Fish and chicken are the most common meats.

- Colorful fashions:

Everyone here wore really colorful clothing,

especially the men.

What looks at first like pajamas is a pants suit called Bomba.

No two are alike.

I bought one, of course.

If you're thinking of visiting Ouidah, be sure to stay at

Auberge Le Jardin Secret.

Nice place. Very authentic.

|

Grinding corn into meal

|

The colorful Rainbow Agama lizard

|

In Benin − and later in Togo − I saw beautiful lizards that I'd never seen before.

These Rainbow Agamas seemed to be everywhere.

Benin's economy is based on fishing, farming and ranching.

It was common to see cattle being driven down the streets of Ouidah.

These odd-looking cows are a hybrid of Indian and European cattle breeds.

They're known for their fertility and resistance to diseases.

|

Nguni cattle going to market

|

|

... and then there are the beaches!

Generally, all beaches are pretty much the same.

Sand, sun, water and surf maybe.

Seen one, seen 'em all, right?

What surprised and impressed me in Benin and Togo was how clean and empty the beaches were.

One doesn't think of west Africa as a beach destination,

but it certainly could become one if enough people found out about how nice the beaches are here.

|

Dugout fishing boat

|

Yachting on Lake Togo

|

Fish nets and traps exposed at low tide

|

I began my visit to Togo with a couple of days on the shores of Lake Togo.

It's a 15 km long lagoon, separated from the Atlantic by a wide sandbar.

This is a nice lake for a swim because

it's one of the few lakes in Africa that has neither crocodiles nor

bilharzia.

|

Independence Plaza and the Royal Hotel

|

Modern shipping containers and traditional fishing boats in Lomé harbor

|

|

From Lake Togo, another shared taxi took me to Lomé, Togo's cosmopolitan capital city.

This is a commercial and shipping center.

To me, the most interesting areas were the fish market and the old center of town,

where the cathedral is.

I went to church on a Sunday morning − as I often do in Africa.

The music was wonderful, as usual.

Does this church brass band remind you of street music in New Orleans?

|

Click on this photo to hear the church band play Gloria in excelsis Deo

|

The elementary school in Ando village, Togo

|

Thanks to a connection I made when I was in Ghana last month,

I joined up with People To People in Togo

for a school-building project in a rural village.

The work was mostly finished by the time I arrived,

but I was pleased to provide some of the funding for the finishing touches.

$1000 goes a long way when labor costs almost nothing.

While in Togo, I was hosted and guided by Newlove Bobson Atiso

(yes, that's his real name)

and his cousin Senna.

Driving around Togo in an air-conditioned SUV was a luxurious way to conclude my west African adventure.

|

|

There's lots more to Togo than I'm showing in my photos here,

or that I had time to see.

If you should you want to visit this little country in style,

I recommend Newlove's Togo Tours.

Click here to see the 11-day Benin-Togo tour which he offers.

For now, this is the end of my journey through west Africa:

- Trip length: 11 weeks

- Countries visited: 15

- Illnesses or injuries: 0

- New friends made: At least 20

- Westerners seen: About 100, mostly in Cabo Verde

- Total cost: $12,750, including airfare to/from plus all visas

- Favorite countries: Cabo Verde, The Gambia and Ghana

- Most memorable lodging: Afrikan Ecolodge in Guinea-Bissau

- Best meal: Christmas dinner at a rustic maquis in Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire

|

Senna and Newlove with their air-conditioned SUV

|

West Africa has a reputation for being an unsafe place to travel because of thieves and corrupt authorities.

In eleven weeks of travel, I had two minor incidents hardly worth mentioning:

- When crossing by land from Ghana to Côte d'Ivoire,

a large man who claimed to be a drug inspector,

searched my bag thoroughly.

He didn't find any drugs, but insisted that a small wooden bird that I was carrying was an "African cultural treasure."

He assessed me a fine of 5000 CFA ($9) for smuggling.

I decided that it would be easier to pay than to argue.

- In the Grand Marché in Lomé,

I noticed three guys shadowing me.

I avoided them for about 10 minutes.

But when they cornered me between two vendors,

a fourth guy slipped up behind me and deftly emptied my back left pocket ...

which is where I keep gum wrappers, used ticket stubs and scraps of paper.

(My passport and wallet are concealed in the zipper pouches of my

lightweight REI pants,

while most of my cash is in my

Eagle Creek money belt.)

I laughed as the pick-pocket hurried away with a handful of garbage.

I attribute my successful journey to being friendly, aware and confident.

Thieves tend not to hassle people who smile, look them in the eye, and act as though they know where they're going.

Nevertheless, I heard one horrible tale from four Taiwanese tourists.

They were searched on departure from Mauritania.

The customs officers found and confiscated 4500 euros from these folks because they hadn't declared the cash on entry into Mauritania.

|

Bye-bye from Benin

|

|

I came to west Africa with low expectations.

Many friends said they had zero interest in this part of the world.

A few friends who've been here say they won't return.

Granted the infrastructure is poor.

It's not easy to find a hot shower, good wifi, cold beer or paved roads.

There are language barriers.

Travel in half of these countries can be difficult if you don't speak French.

However ...

I was pleasantly surprised by west Africa.

What struck me most was the people.

Time and again, I was impressed by their generosity, good humor and hospitality.

Everywhere I went, I was treated very well by open-hearted, honest people.

After all, what makes a country what it is?

The scenery?

The history?

The industry?

The people?

I think we all know the answer to this question.

|

|

|

Having visited more than 100 countries,

I'm often asked which one I like the best.

I can't choose just one place,

so I've nominated my favorites and posted a music video on youtube.

Click here to see my

Top 15.

Click here to return to the world map.

Feel free to email

comments or questions.

|

|